A few weeks ago, Roman ultrabiker Omar Di Felice, Ferrino testimonial, returned from the latest of his incredible adventures on two wheels that took him across the desolate expanses of the Ice Continent.

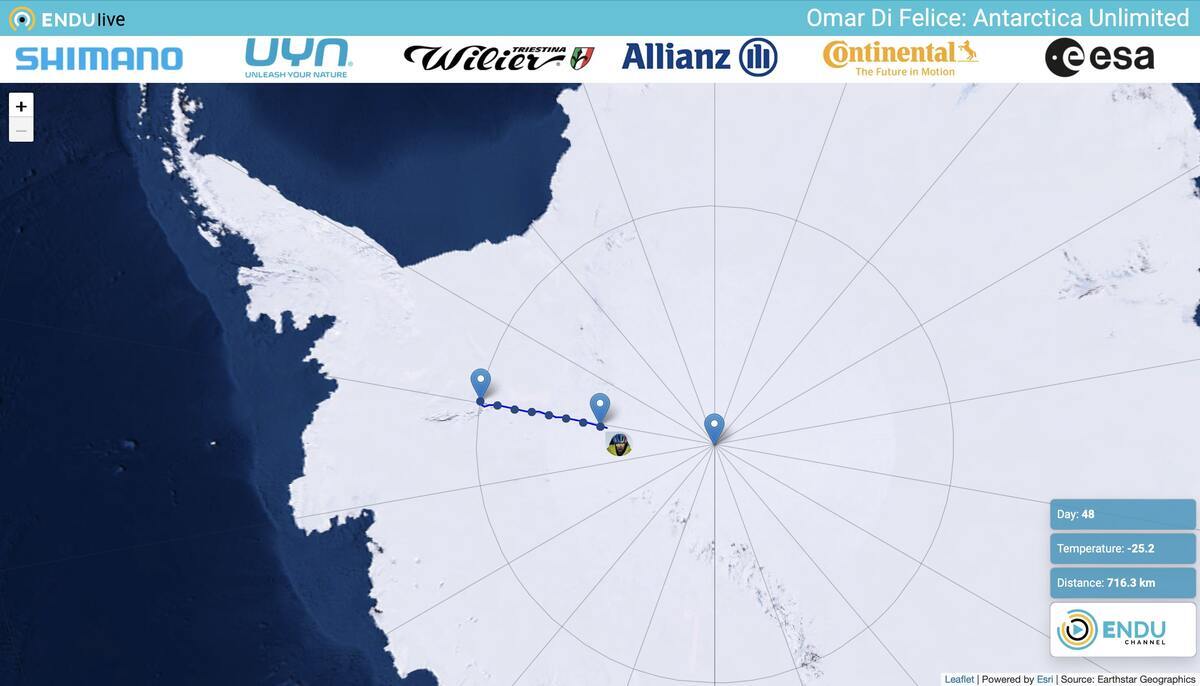

For 50 days and over 700 kilometers he pedaled in total solitude, fighting against extreme temperatures, terrible catabalic winds and the most treacherous snow conditions. Even if in the end the South Pole, the final objective of the journey, remained a distant point on the map, this was certainly one of the strongest and most exciting experiences of his career as an athlete.

This is what he tells us himself.

Omar, you went to Antarctica to reach the South Pole with your bike, which however did not happen. Does this missed goal classify the adventure in the category of "failures", or were you able to bring home something positive from this experience?

Such long and extreme adventures cannot be judged with an out-out. Reaching the South Pole by bike is not a race and in reality it is not even a well-defined goal a priori. It is about crossing the largest ice cap on the planet, something that no one has ever managed entirely with a bike without skis and with respect to which there is no history of other experiences to compare. Already at the start for me this was a great unknown and it would be reductive to define it as victory or defeat only on the basis of reaching the Pole. My main goal was to be able to do the most possible given the conditions I would find; having spent all 50 days of the permits that had been granted to me pedaling and having resisted, lived and survived in those conditions on a bike for me is already worth the definition of personal success.

In your expedition stories you explained that you soon realized that you would not be able to reach the Pole. Despite this, you continued without losing heart. What motivated you to continue? What goal replaced the initial one in your mind?

The change in perspective that allowed me not to give up was replacing in my head what was the ideal timetable towards the Pole with a timetable defined day by day, based on the conditions I found myself facing. Having to pedal with a bike that has a sled of almost 90 kilos in tow, you have to accept moving based on the snow conditions. There were days when I could travel 30 or 35 kilometers and others when the snow and the wind did not allow me to do more than 700 meters per hour. Surely the greatest lesson of this experience was the one linked to the sense of limit: there is a limit dictated by nature that is in relation to our personal limits and those of our technological equipment. From the intersection of these three factors that final number came out: 716, or rather the total kilometers I have traveled and which, as far as I'm concerned, make me totally satisfied with what I have managed to do.

How difficult is it for someone who is used to never giving up to accept the fact that the time has come to say “stop!” and go back?

If I had reasoned in a “traditional” way during the crossing, I probably would have given up much earlier, I would have become depressed and I would have defined this adventure as a defeat, a failure. In reality, when you move in these conditions you take the good that comes from it, you learn what the territory is giving you and you accept the fact of doing the most possible. If I returned to Antarctica next year, perhaps I could travel a few more kilometers or maybe reach the South Pole, or even less road than the one I traveled this time. But these are outcomes that would not depend exclusively on me. As I have already said: there I found the limit and I gave 100% to get as close as possible to it, the rest is entrusted to the astonishing power of the Antarctic nature, over which you can have no control.

You have stated several times that Antarctica has turned out to be something totally “other” compared to everything you had faced up to now, even compared to the Arctic environment that you had already faced in the adventure between Canada, Alaska and Northern Europe. What makes it such an extreme and special place?

Antarctica is a place alien to the rest of the planet. I have been to northern Canada and Alaska. I have been to Greenland, in remote areas where for 100 or 150 kilometers there is not even a shadow of an animal. However, nothing is comparable to Antarctica, not so much for the weather conditions, but for the living conditions and isolation. Down there you are completely alone for hundreds of kilometers and if something were to happen to you you would not be sure of being recovered in a few hours. This idea is instilled in your mind from the first step you take and makes everything different. Whatever you do you know well that it could be fatal. Even the most banal accident can generate catastrophic consequences. While I was on an expedition for example I was in contact with a boy by satellite phone who was attempting the crossing on skis. At a certain point he started to feel sick: he couldn't urinate. It was a very stupid problem with kidney stones, something that in normal situations is resolved with a hospital stay of a few days. But getting him out of there and taking him to base camp and then to a hospital in Chile was truly an extreme feat!

You spent dozens of days alone in vast landscapes, on an almost uninhabited continent. What happens when you experience such immense solitude, even difficult to even conceive?

Living in this condition makes you change your perspective on things. It is one of the reasons why I say that I cannot look at this experience in terms of defeat or victory. In an environment so large and so dominant compared to what your possibilities are, you really understand how much nature is bigger than us and how it is also the case to review a little what our possibilities are. It is an experience that teaches you to respect nature and also yourself. After all, in everyday life there is little time that we spend alone with ourselves; there are very few times that we stop to reflect, without having any external conditioning. When you spend 50 days in Antarctica, completely alone and talking only to yourself, then this intimate and vital comparison is brought to maximum power.

You said that for you Antarctica is a closed chapter and that there you experienced that there are limits that it is not right to exceed. It is a very interesting statement, especially because it was made by an ultra-athlete, that is, by someone who has somehow made exploring and exceeding the limit her reason for living. Perhaps, however, it is not a consideration that only concerns your sporting philosophy, but has an even broader and deeper meaning. Do you want to talk to us about it?

We all grew up with this rhetoric of ultra, which means going beyond every limit, at any cost. And this at any cost, in my opinion, is what is out of place. It is right to explore one's limits, it is right to get up from the couch and take a step further than what we think we are capable of doing. This is certainly what moves and motivates me every day, it is my constant research: always trying to understand what my limits are and always take them a little further. However, in doing so, you must not live this overcoming as an obsession. The limit must not be exceeded at all costs and, above all, the limit exists! Saying "if you want you can", always and at any cost, is a perverse idea. In Antarctica, which is the most remote and extreme place where someone can think of having a cycling adventure, I knew that I would find a limit somewhere and I also learned to accept it, returning home satisfied with having given everything I could give, respecting the limit itself and my life.

Probably in this expedition even more than in the previous ones you had the chance to test Ferrino's technical materials. What equipment did you have with you and how did they behave during such extreme and prolonged use?

To be honest, in preparing the expedition we didn't work too much on customizing the equipment, trying to develop something special, designed specifically for the expedition. I relied on the technical products that Ferrino has in its catalog, already extensively tested for use in extreme conditions in the outdoor environment. I had the Blizzad tent with me, already a trusted companion on many expeditions, to which we only made a few small changes to make it easier to assemble and dismantle with the terrible Antarctic winds. Then the Revolution 1200 down sack, the best of the series in terms of thermal insulation power, and a series of coupled inflatable and non-inflatable mattresses. What made the difference for me, confirming the reputation that Ferrino has earned over the years, was total reliability. When you have to spend 50 days alone in Antarctica you need to have the peace of mind of knowing that the tent won't tear, that the pole won't break, that the mattress won't literally leave you on the ground... On this, once again, I have to give top marks to Ferrino: from the first to the last day, its equipment ensured that I could do what I was doing safely and never leave myself truly exposed. In fact, all the materials returned home completely intact and without any kind of damage.

Do you want to meet Omar and ask him some questions in person? Come to the Ferrino Store Torino (Corso Matteotti 2L, Torino) to meet him, Tuesday 13 February at 18.

All the behind-the-scenes details of Antarctica Unlimited, the 700 km expedition, two months in the saddle, at -30 degrees and with a tent as the only point of support.

Free admission.