THE SONGS OF THE SONGS

In the beginning of time, Australia was a flat, lifeless land. Vast entities descended from the sky, came from the sea, and emerged from the bowels of the earth. With their arrival, Creation began and life began to pulsate. As they moved across Australia, the entities shaped the land with their bodies, creating rivers and mountain ranges and forests full of life. In everything they touched, they left a part of themselves, making every corner of the world sacred to those who knew how to look. In the east, Biame reached Sydney Harbour, shaped its shoreline, and having completed his work, he headed for the mountains, from where he returned to the sky. His path shaped the bed of the great Parramatta River, and his farewell to the land raised the Blue Mountains from the ground. Time began to flow, and with it the water of the river, from the mountains to the bay.

The first men began to inhabit the earth: the Aborigines. Their ancestral wanderings scattered them across the territory like breadcrumbs on an immense table. They remained faithful to the nomadic nature of their Ancestors, they became hunters and gatherers, and in a life without enthusiasm they chose to celebrate their home by sanctifying the places they learned to recognize. For forty thousand years they knew and remembered every corner of Australia, without maps or roads, and by singing its stories they gave voice to the Songlines. In the looks, between the lips, in the collective memory of hundreds of populations, these timeless songs guided the steps of the Aborigines in the first pilgrimage in human history: the Walkabout.

Walkabout was the way the Aborigines moved around the uninhabited lands of Australia. Having no writing, they relied exclusively on oral traditions, learning where to go and how to get around thanks to their songs. They indicated where to find food, at what time of year, how to orient themselves in the desert and when to move according to the season. The Songlines marked the position of every tree, rock and horizon, vestiges of the footprints with which the Ancestors had shaped the land. The whole of Australia, an area as large as Europe, was “mapped” with countless songs over the course of tens of thousands of years, creating a dizzying connection between the land and its inhabitants. The arrival of the English colonists, in the late 1700s, wiped out this culture in the space of just two centuries. Now, along with the Aborigines, even the invisible traces of the Songlines are disappearing. The ancient tales have withered into scattered and disconnected words, but what remains still has the power to suggest and some traces have fortunately managed to survive.

THE WAY OF THE OCHER

The Arabana were a tribal group settled north of the present metropolis of Adelaide, the capital of South Australia.[1] They lived in a territory rich in ochre, a material used as a pigment in cave paintings, in medicine and for ceremonial purposes. The ochre was bartered with populations near and far, and over time a Songline was given voice that crossed the country from south to north. The trade route snaked through the Outback, the gigantic desert sitting in the centre of Australia, eluding temperatures that in summer touch 50 degrees and providing a reliable route for three thousand kilometres, all the way to the far northern reaches.

The Way had been sung for forty thousand years and in 1860 it was translated by interpreters to John McDouall Stuart, a Scottish adventurer. Relying on the knowledge gained from the natives, Stuart embarked on a series of adventures that culminated in crossing the country, becoming the first Western explorer to penetrate the heart of the desert and reach the shores of the Indian Ocean. This was a turning point for modern Australia. Based on Stuart's information, the railway and telegraph lines were built. Adelaide and Melbourne finally had a direct link to Darwin and its port on the Asian coast.

Before then it was necessary to circumnavigate the whole of Australia. It is difficult to make a comparison with Europe, but if we were to consider only the distances, it would mean that between Lecce and Oslo there were no roads but only a boundless land without obvious points of reference and the only way to go from one to the other was to go around the continent sailing through the Mediterranean, the Strait of Gibraltar and finally going up the west coast until reaching the destination. The distances of Australia are impressive and to grasp them requires a considerable effort of imagination. Alternatively, you can rediscover the furrows left by Stuart and the Songline of the ochre by joining remote dots on the map and setting up meticulous logistics to face the indifference of the desert. Only by walking can you realize the immensities that nomadic populations have embraced; therefore it is by walking, between May and September 2023, that I tried to experience them.

RUNNING-IN

I arrived in Adelaide after a considerable run-in. I had left Sydney, on foot, a month earlier, so as to gradually enter the Australian orders of magnitude before tackling the desert. Sydney lies to the east of the Blue Mountains, beyond which, for hundreds of kilometers, fields of wheat, barley, lupins and lentils compete to push the horizon ever further away. The cities had slowly diminished into isolated villages, then into inhabited centers with a few dozen people.

The first few weeks were reminiscent of the journey through the Argentine Pampas. Wide expanses of square land and endless pastures, few four-legged animals, fewer men, and so much sky. The Latin American estancias were now called stations, a different name that tells the same story of stubborn settlers devoted to raising sheep and cows. A single road stretched to the end of the line of sight before disappearing into perspective. This time, however, there was no imposing outline of the Andes to dictate boundaries. The white trunks of the eucalyptus had replaced them and from their rustling foliage the birds sent out their calls. I learned to recognize the laugh of the Kookaburra and the ethereal cry of the Butcherbird, the trill of the green parrots and the white flash of the cockatoos. The monotony of the landscape highlighted its sounds and movements and it made me think that perhaps the Songlines had been inspired by them to give voice to the known world.

In the 1,400 kilometers between Sydney and Adelaide, I noticed a recurring element: every village had a minimal post office. Sometimes the same service station, an essential lifesaver for vehicles venturing onto these endless roads, served as a mail receiver and dispatcher. This was an important detail, because on the next part of the journey I could send food to the points through which I would pass. Even with Ezio, the stroller that carries everything I need, it would not have been possible to stow enough supplies to cross the entire desert.

FINAL PREPARATIONS - WITH BEARING BREATH

Adelaide was the last big city I would pass through. After it, Darwin. Three thousand kilometers separating them and a single significant town in the middle, Alice Springs, the capital of the desert, just twenty thousand inhabitants but, crucially, a supermarket where you could stock up. From Adelaide to Alice Springs it would take me two and a half months, walking at a rate of 40/45 kilometers a day - ten hours including breaks. I calculated roughly one day of break every ten. The visa time left little margin and to take advantage of the winter and avoid the fifty degrees of the other seasons, I would continue at a fast pace.

I decided at the table what I would eat for the next few months, at every lunch and dinner. Convenience and energy intake were important, flavor was secondary. For lunch I bought six kilos of rice and quinoa, for dinner two of lentils and two of vegetable proteins. I stocked up on oats, powdered milk and cocoa for breakfast, and for snacks dried fruit, honey, peanut butter and chocolate. Bags of freeze-dried fruit and vegetables would at least partially make up for the lack of fresh vegetables.

It was unwise to rely on what I could find along the way, so I set out with the idea that I would buy little or nothing for the next few months. Ezio was over a hundred pounds when we first set out toward the outskirts of Adelaide. In addition to food, he carried about ten liters of water, which in winter temperatures was equivalent to five or six days of autonomy; a small pharmacy, complete with bandages and remedies for snake venom; spare parts, a solar panel to charge electronic devices, a gas and petrol stove with their tanks. May was almost over when we set out to follow Stuart's trail into the desert and into ourselves.

The road led away from the coast, heading north-east towards the Flinders Ranges, a low mountain range that extends 400km to the north. Stuart used this as an initial reference point as he headed into the vast unknown distances of the further regions. The presence of the mountains moderated the climate, protecting the area from the extremes of the interior. The eucalyptus were still thriving and in the mornings the tent was damp. I passed almost one human settlement a day, but as I continued the signs of human presence became sparse. For long hours, the only tangible sign of human presence was the road I was walking on. I managed to keep my supplies stable but the wait for the desert became unnerving. I was waiting with trepidation to confront him.

I remembered walking through the Atacama Desert in Chile a year earlier. One lesson I had learned was that connecting to its dissolution takes days, sometimes weeks. The longer you stay in the desert, the deeper you can dig. Knowing yourself is a dizzying sensation and at times, in an unexpected reversal of perspectives, nostalgia would remove its cloak from home to envelop the time spent inside the Atacama. Its still spaces suggested ideas of infinity, death, god, beauty, stillness. Nothing else could dwell among those gray stones. Like eternal guardians, they offered the mirror in which to observe one's own frailties: those of man as an extra and of the human as mortal.

OODNADATTA TRACK

It took three weeks to reach the edge of the desert. The road ended abruptly at the village of Marree, twenty souls in all, leaving a dirt track to guide me. The service station was a dimly lit little hole that offered food that had arrived weeks earlier with the last truck. The prices were prohibitive and the selection was very limited. The back of the shop was given over to spare parts for cars, motorcycles and bicycles: inner tubes, puncture sealants, a few screws, some cellophane-wrapped cloths. Near the cash register were displayed some tourist items, among which were faded postcards and stickers. One of them read: WHERE THE HELL IS MARREE?

I smiled for a moment, then my eye was caught by a green patch with a yellow border, the kind you sew onto a backpack to give it a switch to flip when you try to make conversation. The patch was a simple script, with numbers written in small letters underneath. The script: OODNADATTA TRACK. The numbers: WILLIAM CREEK 204 - OODNADATTA 406 - MARLA 613. A sinking feeling settled in my stomach. The numbers were distances, how far I would have to walk over the next few weeks to get from one point on the track to the next, little more than names on a map. The mileage was calculated from where I was at the time, the town of Marree, the start of the Oodnadatta track.

The Oodnadatta track is the route that has undergone the least changes compared to the route taken by Stuart one hundred and fifty years ago and in fact represents the most authentic, difficult, immersive and alienating part of the Explorer's Way, the road that retraces the explorer's steps through the Outback. A few years after Stuart's enterprise, the telegraph and the steam train arose along the track, encouraging the development of some modest stations to operate the railway line. It was Afghan migrants, among others, who built the tracks; and it was the Afghans who first introduced camels to Australia. The arid environment was congenial to them and they were soon used extensively to transport goods along the desert tracks. The railway line was later named The Ghan, to pay homage to the Afghan contribution to its construction.

The train ran for a century, until 1980, when it was moved west, alongside the current Stuart Highway, the asphalt snake that runs from Adelaide to Darwin by the straightest route. The relocation of the line led to the death of the stations: deprived of work, people fled from such hostile and isolated environments. Only two towns survived the decline: William Creek and Oodnadatta, the names that the green patch spaced over two hundred kilometers apart.

From the information of those who had ventured there with off-road vehicles, I had an idea of the conditions of the track and I doubted that I could keep up the pace maintained until then. In my head, two hundred kilometers became five days of walking, maybe six. In between, the anthropic nothingness. No kind of infrastructure apart from some rusty wrecks of the railway, no supplies. Three times, two hundred kilometers at a time, there would be only the track, the desert and Ezio. The world would shrink to the present and what I needed would shrink to the point of fitting exclusively into a stroller. Things were starting to get serious.

The night before leaving, I played dice with some guys I met in the village, contemporary migrants from Italy, Chile and Argentina. Inside the container used as a kitchen, Spanish and red wine sat with us around the table of fortune. We tried our luck while the night enlarged the hours; when they were about to shrink, we went to sleep. The sleeping bag welcomed me generously, as always, but I slept little, as often happens on the eve of important departures.

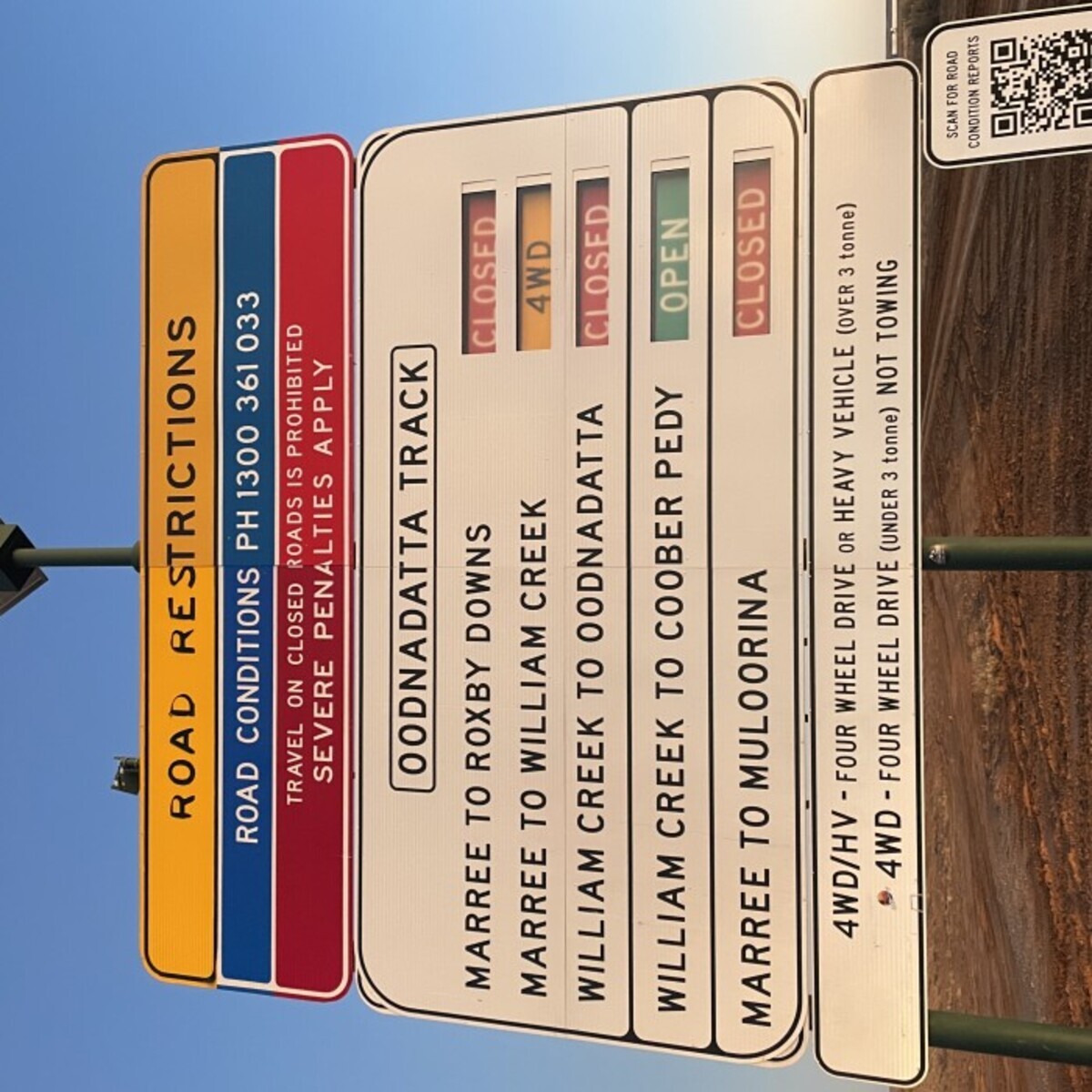

To take advantage of all the hours of daylight, the alarm was set for five-thirty in the morning; half an hour later I was on the road. Past the village, the line of asphalt faded into the fine earth. A tall sign, straddling it, announced alarmingly that the runway was closed, while to the east the aurora colored the early hours of the day pink and orange; there were no shadows between us and the sun.

INSIDE THE SILENCE

I set off resolutely north, beginning to observe and mentally note the road conditions. I was just thinking that the stories, as usual, had exaggerated the difficulties of the track, when Ezio suddenly slowed on the right side, as if held back by an invisible force. I moved my gaze to the side, sliding it to the wheel: punctured! The sharp tip of a spinifex was sticking out from the tire. The earth was a mixture of dried mud, shrubs and salt crusts that hid threats beneath its hard shell. After the replacement, there were two inner tubes left for the rear wheels and two for the front; among the spares there were also patches and tire glue, so for the moment I could rest easy; but the fact that I had punctured after just two kilometers was a discouraging sign.

The first day serves to calibrate the estimates made at the table: what to do if they are wrong? Going back requires humility, at least as much as moving forward requires courage and trust. A puncture, in an environment like the desert, makes you perk up your antennas and continue with extreme caution, with tense muscles and eyes darting from one side of the track to the other as if it had suddenly turned into a bed of broken glass. As the weeks passed, Ezio would lighten the weight of the food, thus exerting less pressure on the wheels and therefore decreasing the probability of a puncture. However, it would happen slowly, at the rate of half a kilo a day - the water could be considered constant because it had to be refilled at each station.

I thought all this as I pumped air into the new inner tube, and I would repeat it every morning, like a litany, for the next few weeks, updating the supplies I had left, the weight Ezio was carrying, and every tiny variation that gave me something to counter the pressure the desert was exerting on my mind and body.

The rest of the day went smoothly. Around four o'clock the GPS showed forty kilometers, a reasonable figure. I started looking for a place to camp and a hill covered in rocks seemed like the ideal place to pitch the tent. The last effort of the day was the bumpy climb to the top. I had not calculated the rough terrain and removing the rocks from in front of Ezio took longer than expected. When I reached the top, however, the view was sensational.

The landscape was utterly banal, devoid of lofty mountains or bright colors. Yet the day’s sweat and, finally, the hill, had clothed those dark rocks with the aura of beauty. The effort had drawn a veil before their eyes and the world they were observing seemed to have acquired a meaning and a quiet that could not exist elsewhere. Behind the hill, to the south, a strip of land with raised edges suggested the origin of this unusual pilgrimage. On the opposite side, the track disappeared behind yet another hump, devoured by the soil. The place had no name, nor a number to officially indicate its position in relation to Marree. Even if one described it in detail or showed a photo, that place would be unfindable to anyone who tried to reach it; and even to those who had the exact geographical coordinates it would remain unknown, because when I arrived there, tired from the walk, I was in the right frame of mind to stop and appreciate it. I liked to think that I was probably the first person to rejoice in that insignificant corner of the world.

A NEW DESERT

The quantity of flowers that sprouted on the edge of the trail was impressive. I soon learned to recognize them, even though I didn't know the names by which they were classified. Yellow and purple were the dominant colors; then white and red. There was a flower with a pink and green corolla in the shape of a rosette, a yellow center, and touching it left the delicately wrinkled sensation of tissue paper on the fingertips. A shrub with green and fleshy thorns showed off a spherical yellow pom pom similar to a mimosa while at its feet the daisies had gathered fire in the center of their petals and spread a tea tree scent that was exaggeratedly intense for their small size. I looked for them with my eyes especially in the afternoon, when I was more tired, and it seemed like I was meeting friends I had just met. Making an appointment with them made little sense: they would suddenly appear, a few steps away, shaking their heads to follow the wind.

The hours stretched out and the days took on an oppressive density, blurring and separating according to the degree of concentration. Was there any point in distinguishing them? At times it seemed not, in fact taking them into account made you feel tired; but not doing so seemed like going mad, lost in a formless time that spoke no language. Lake Eyre appeared for a few hours at dawn on the third day; or was it the twilight of the fourth? The night I camped in front of it, a long howl made the night shiver, followed by mournful echoes. It was the greeting of the dingoes, the wild and free dogs of the desert. Why is there a lake in the desert? And how do you explain the flowers?

The Outback is a land of contrasts. Although its surface is inhospitable, thousands of metres below ground lies one of the largest artesian aquifers on earth, the Great Artesian Basin. This is a freshwater reserve that was created millions of years ago from an inland sea in what is now Australia. The underground reservoirs contain billions of litres of water and are replenished annually by the rainy season that plagues the tropical regions to the north. The water infiltrates for kilometres through the permeable soil and ends up in the bed of the artesian basin. In some places there are upwellings that feed springs: this is how life survives in these deadly areas. It was thanks to the springs that the Aborigines were able to establish the Ochre Songline, verbally noting the position of each of them; and it was thanks to them that Stuart was able to cross the desert for the first time.

Lake Eyre today is a crust of salt unfit for life, a witness to an extinct sea. The water reserves are buried two thousand meters below the ground and it is rare to see an active spring. However, I can call myself lucky. In recent years the rainy season has been particularly abundant and from the north the torrents have come to bathe the heart of Australia. For once, paradoxically, climate change has favored life.

WITHOUT BREAKS

As the days went by, the loneliness deepened the feeling of alienation. My spirits began to swing on a swing and at times it seemed that the distance left was too great. Despondency sat on my chest and weighed on it, knowing that I had nothing to counter it to distract me. I had been walking in the Outback for months and I had not yet covered half the distance. Reaching Darwin seemed too, too far away. Months. There were three more months to go. The surface of the track had become uneven and made progress slow and painful. The wind also contributed, unexpected, and eerily reminiscent of the angry gusts of Patagonia, constantly pushing against the direction of travel. There was not a day that blew in my favor.

I arrived in the evening exhausted, with heavy muscles, and once I had chosen where to camp I had to be on guard to check for spiders or poisonous snakes. Once, when I placed the tarp on the tent, a hairy spider the size of the palm of my hand appeared, running neurotically. It was disgusting. I tried to move it with a dry branch, but it slid away undaunted and with extreme horror disappeared under the basin. It was impossible to flush it out. Disturbing images projected it crushed and bloody under my back, or waiting for the complicity of the darkness to slip next to the only source of heat in the vicinity: my prone human body. The thought alone made me shiver. Keeping my imagination in check is especially difficult when you are tired, alone and in a hostile environment. But precisely because I was alone and in a potentially deadly environment I could not let despair get me down.

After five days of walking, the track returned to asphalt for a blessed thousand meters. I had arrived at William Creek, the first outpost on the Oodnadatta track. A pub, flanked by a petrol pump and a hangar that stored propeller planes, were the only buildings. Because of the isolation, places like this have a charter runway. The planes are used for refueling, emergency rescues of people who, lost in the desert, manage to send out a distress signal and, in some cases, even for tourism. I drained two liters of cold water and tucked into a hot and tasty meat pie, the typical Australian meat-filled pastry. It took a good two hours to load the GPS; then it was time to get back on the road.

METHOD IS NEEDED

I had only covered a third of the track but the disconnection seemed to have been going on for weeks. It took another ten days to complete it and return to a glimmer of humanity: a paved road, a few road signs, an occasional truck. The internet connection remained absent, leaving room for internal dialogue. I realized that I needed to stick to a method if I didn't want to go out of my mind and lose concentration. The challenge became grinding out kilometers according to a set plan: regular breaks, no variations and focus on the immediate future, the stages from here to a week. I momentarily put aside the idea of getting to Darwin and finally entered the desert, embracing the route day after day. My mind wandered, daydreaming about stories and trips in minute detail. But it also became natural to silence my thoughts, let my legs go on their own and look at the clear blue sky for hours and hours, clearing my mind and trying to imitate it.

They were moments of total peace that made you want to live forever in the open air and sleep in a tent and eat while looking at the horizon from the edge of the road. Standing under the immense sky filled me with joy. A powerful sense of freedom began to pulsate in the air because, finally, I had reached a balance. The desert had entered inside me. It had dug a hole and then suggested how to fill it: to climb back up the abyss it was necessary to let go of things and people and reach the pieces of identity that you thought were clinging so tightly that it was impossible to give them up. Yet roots can be cut. From the initial disorientation you move on to anguish due to a lack of points of reference, the colors take on dark tones; but after getting lost, you find yourself again, and you observe that even if everything inside has changed, outside things still happen the same way. Freeing yourself from the narratives that have formed your identity brings you closer to your essence. Freedom is such that, if you want, perhaps it is even possible to go back. Time knows the only answer; and he hasn't wanted to tell me yet.

The remaining months continued slowly, keeping Ezio and me company. We walked for thousands of kilometers more and took a two-week detour to pay homage to Uluru, the sacred monolith of the Aborigines, guardian of the myths and legends of creation. Once we reached Alice Springs, we rested for a few days. The time for the visa was ticking inexorably. Towards the north we celebrated twenty thousand kilometers and three years on the road, far from home. Nostalgia accompanied our steps, finally in silence, accepting its place in the choice to travel around the world on foot. Darwin was a long-awaited gift, without surprises, like the prizes that are obtained after an effort so intense that it has taken away even the desire. We touched the Indian Ocean with hands, shoes, wheels and feet. We watched it flatten and make room for the sky, mixing the blues in a distant horizon. We had crossed the Australian desert. And after six months and six thousand kilometers, the journey in Australia ended.