My nerves are in tatters. Behind me, a sheep bridge runs from one side of the Carreras River to the other, a hundred meters of bated breath that I had to cross five times to carry Ezio and the equipment from one bank to the other. Now I find myself in a scree just after the bridge, exhausted, and there is no sign of which path to follow. In the last six hours I have traveled just seven kilometers and night is falling on no man's land preventing me from moving forward. The clouds are condensing on the horizon, I feel the ticking of the first drops of freezing water hitting my jacket. Although I am exhausted, I have to set up camp before the storm arrives. I choose with a clinical eye the flattest rectangle, I clear my way through the rocks, I lay down a black plastic sheet to isolate myself from the ground and finally I set up the house that has protected me from the wind and rain for the last eight thousand kilometers: the Ferrino Manaslu 2 tent is the orange lifeline in which I will find refuge again tonight.

I am crossing the border between Chile and Argentina at the Mayer Pass. Once the Carretera Austral was completed, I was planning to exit the country via the Candelario Mancilla Pass, but even though it is November 2022, the border has still been closed since the Covid era - damn bureaucratic delays… The only viable alternative, considering the visa times and the commitment to complete the journey on foot, was to head north, to the infamous Mayer Pass. It is just fifteen kilometers between the Chilean and Argentine checkpoints, yet the path is disgustingly bumpy. River crossings, swamps, cattle fences to cross, the dirt track that repeatedly disappears into the brambles, in hindsight you are proud to call it an “adventure” but when you are there cursing the laziness of the border soldiers the only adjective that comes to mind to describe it is: CRAZY.

I set up the tent in a few minutes with the experience gained from hundreds of campsites. Basin - front arch - fork arch - waterproof sheet - pegs - wind flaps turning counterclockwise, guy lines, anti-condensation vents front and back. I open the zipper that seals the entrance and continue the sequence, I could do it with my eyes closed. I lay out the mattress on the right, unscrew the inflation valve and listen to the familiar hiss indicating that the air is entering my portable bed - the self-inflating mattress is a gem. Sleeping bag on the side, followed by jacket/pillow, backpack with the technological elements and the only change of clothes I carry with me, lunchbox for dinner and breakfast, water, toothbrush and toothpaste. I should do some stretching but this time I am at a minimum. I sit in the tent and clean the wounds on my calves with sanitizing wipes, the bramble bushes crossed during the day have drawn a dark red arabesque on my skin. There are eight kilometers to the Argentine border control, I think as I collapse on the mattress. If it continues like this, I will arrive there in another two days and the supplies I had calculated will suffer a major cut, enough to have to rethink them for the following weeks. I set the alarm for five, the northern summer is approaching and the days are getting long, with 15-16 hours of light. Will I make it to Argentina?

The next morning the alarm finds me already ready. It always happens when I feel that the day will be busy. Ezio and I set off well before six, avoiding rocks and ditches for the first few hours of walking. The fording of a couple of shallow rivers wakes me up completely, the water is frozen, we are in the Andes; however, the route is decidedly better than yesterday, we manage to proceed quickly and at ten we breathe a sigh of relief. We have reached the gendarmes' guardhouse! The vaccination certificate is not requested, I just hand him my passport, “Cuanto te quedas?” “No se, un par de meses a lo maximo” “Dale”, the officer slaps his hand on the stamp and I raise my hands to the sky. It's official, we are in Argentina!

It’s been two days since I left Villa O’Higgins, the last outpost of the Carretera Austral, to head to Chaltén. I’ll have to cover a 500km detour that will cost me two weeks of walking. The goal? To visit the trails of the “National Capital of Trekking” in Argentina. Since I’m walking around the world, it seems sensible to extend the route to add extra kilometers! So here I am in the infamous Pampa, a land battered by incessant winds that reach a hundred kilometers per hour. Little grows in these desolate lands: low shrubs, grass with resistant roots, a few trees along the rivers that descend from the Cordillera. Ochre and gray are the predominant colors, signs of drought. And yet, even in this hostile environment, hundreds of travelers launch themselves every year along the gigantic distances that separate the small inhabited centers of Patagonia, pedaling and driving in search of suggestive panoramas and experiences to tell. Just as in Chile the Carretera Austral is the page on which to write one's adventures, in Argentina the book to be popularized is the Ruta Nacional 40, a five thousand kilometer road that runs from north to south of the country and which is affectionately called the 40.

And as if they had been waiting there, as soon as I set foot on the asphalt of the 40 a couple of German girls on bikes come towards me. It's the fifth day at O'Higgins and I'm without a connection, so after the warm greeting I ask for information on the weather. On this side of Patagonia the rain doesn't matter much: when does the wind blow? In which direction? It seems that for the next two days it will sleep, from the third it will start to howl in an obstinate and contrary direction until the weather forecast gives visibility. I do a quick calculation, I can reach the intersection with provincial road 29 and cut 70km before the wind starts. That way, if it were too strong to continue, I would still have a buffer of 70km/two days on supplies. But then, I think out loud as the girls move away, how strong do you want it to be to stop a person pushing a 50kg stroller? In two days, I would find out.

Punctual as the night, Eolo shows up on the afternoon of the seventh. Massive gusts swell the black tarpaulin covering Ezio and raise whirlwinds of dust from the desert that surrounds us. The surface of provincial road 29 is unpaved, I have a better grip on the ground but I have a harder time pushing Ezio, he is carrying ten liters of water so I can cook something hot to throw in my stomach. I am calm, I was waiting to see how strong the wind was and for the moment I can keep going. With difficulty, of course, but if it continues like this I can make it on schedule and get to Chaltén in two weeks. I am halfway there, I am doing well. I keep repeating it all afternoon, encouraging myself with simple calculations that show how I have already traveled most of the way. I camp in the middle of nowhere, waiting for the breaks between one gust and the next to lay out the tent and bend the poles to give it shape. I plant all the pegs, pull all the guy ropes and position Ezio so as to protect the camp. Even so, the sound the jolts make is chilling: it feels like a giant is punching the outer sheet, making everything vibrate and bounce. There are still seven nights left to reach our destination and if the structure gives way I would have to spend them out in the open. It would be impossible to sleep with this wind, I can't imagine how the hell I would manage to reach my destination. But the Manaslu knows its stuff, it is flexible and follows the wind without breaking. I sleep little because of the roars that are unleashed with each blow, but I manage to recharge my batteries. At dawn there is silence, the wind has been standing all night and is now resting. Better to take advantage of it and cover the bulk of the stage while it is not there.

The days continue with ups and downs. Once Aeolus forces me to give up, blowing so hard that I can't go any further. So it's true, the wind can stop a boy pushing a 50kg stroller. I find shelter under a fence that crosses the road, I wait for the gusts to decrease to pitch the tent and it's only at sunset that I manage to set it up. In a few days I'll reach Chaltén, I just have to hold on and walk with the wind howling in my ears. I'm amazed by the intensity of the air currents: for days and days they blow incessantly, without any respite. At night they interrupt my sleep and during the day they lower the temperature so much that I have to wear gloves and a wool balaclava. The dust irritates my eyes and ends up in my food, every movement is made with caution and even - natural, but you have to be careful - even peeing becomes a balancing act. Despite the exhausting conditions, the Pampa desert is a perfect place to think. Once the wind's cry and its slaps have been assimilated, there are no distractions: with touch, sight and hearing overwhelmed by the air, the mind turns inward and probes the depths of the soul in a journey longer than the world. What is boredom when every minute is devoted to a different thought? This is the treasure of solitude: oneself.

I arrive in Chaltén almost with melancholy, at the end of the fourteenth day. I am physically exhausted but in my head and soul there is peace. Who knows, maybe a few more days would have done me good… I set up my tent in a campsite and spend the first two days absorbing energy from food. Eating is one of the most satisfying parts of a trip like this because I can gorge on quantities of butter and dulce de leche sandwiches without restraint! While I replenish my fat reserves, I gather information about the pueblo. Chaltén enjoys a skyline that is very famous in the mountaineering world, formed by unmistakable granite mountains: Fitzroy, Poincenot and Cerro Torre are some of the most evocative names for those who love the mountains. There are several trails that lead to exploring the sharp spires and the glaciers stretching beneath them. Those to Fitzroy and Torre can be done in a day, while some more challenging ones require a minimum of preparation. One of these is the Vuelta Huemul, a four-day counterclockwise circuit around the peak that gives the trek its name, Mount Huemul. The route is simply astonishing: for the first time I walk on a glacier, camp in a bay full of icebergs and, as if that were not enough, I cast my gaze over the legendary Campos de Hielo, an immense expanse of ice of impenetrable nature. The Campos exert on me the evocative charm of the uncontaminated because only one expedition has managed to cross them in total autonomy. Only one, in all of history, you understand? In Antarctica there must have been at least fifteen, not to mention the North Pole. The extremely harsh weather conditions and the largely unknown morphology make it one of the last intact places left in the world. No scientific basis, let alone tourism, have managed to dent its peace. It is an indescribable emotion to get close to them and feel the power of their fifty glaciers welded together by thousands of years of isolation. These are also the last days of camping with the Manaslu, it seems like a worthy farewell to the tent with which I crossed Peru, Chile, the Atacama Desert, the Carretera Austral, and trekked among ancient Inca ruins and wonderful snow-capped mountain ranges, up to 5000 meters. Together with the Ferrino Team we decided to let it rest and replace it with a “youngster”, the newcomer in the assortment of 4-season tents: the Namika 2. How will it get to Argentina? You won't believe it but even… My father will come to bring it to me! In reality we had decided months ago that he would travel part of the world tour with me and fixed the stretch in Argentina, between Chaltén and Calafate. Taking advantage of his arrival, he would bring the new tent along with some other spare parts, both for me and for Ezio: after 14,000 km, my companion needed a pair of new tires.

And so, on December 3, 2022, at the bus station in Chaltén, I hugged my father again. He had just come from a trip of almost three days but he wasn't tired in the slightest. In my family, we call him the bionic man for the infinite energy he has and in the following days he immediately showed the grit he had brought from home. To tell the truth, his strides left me behind most of the time and I found myself laughing alone, trotting behind his silhouette to try to catch up with him. After a few days in the mountains, we got back on the road towards El Calafate, the charming village. The first day after saying goodbye to Chaltén fell on my birthday. Having dad walking with me was the best gift I could have dreamed of but, the icing on the cake, that evening we toasted in the tent with a Dalla Vecchia grappa, I think it was a Prime Uve. We passed the cordial around, sipping it patiently, savouring the aromas of home with the calm of those who can appreciate the little things in all their significance.

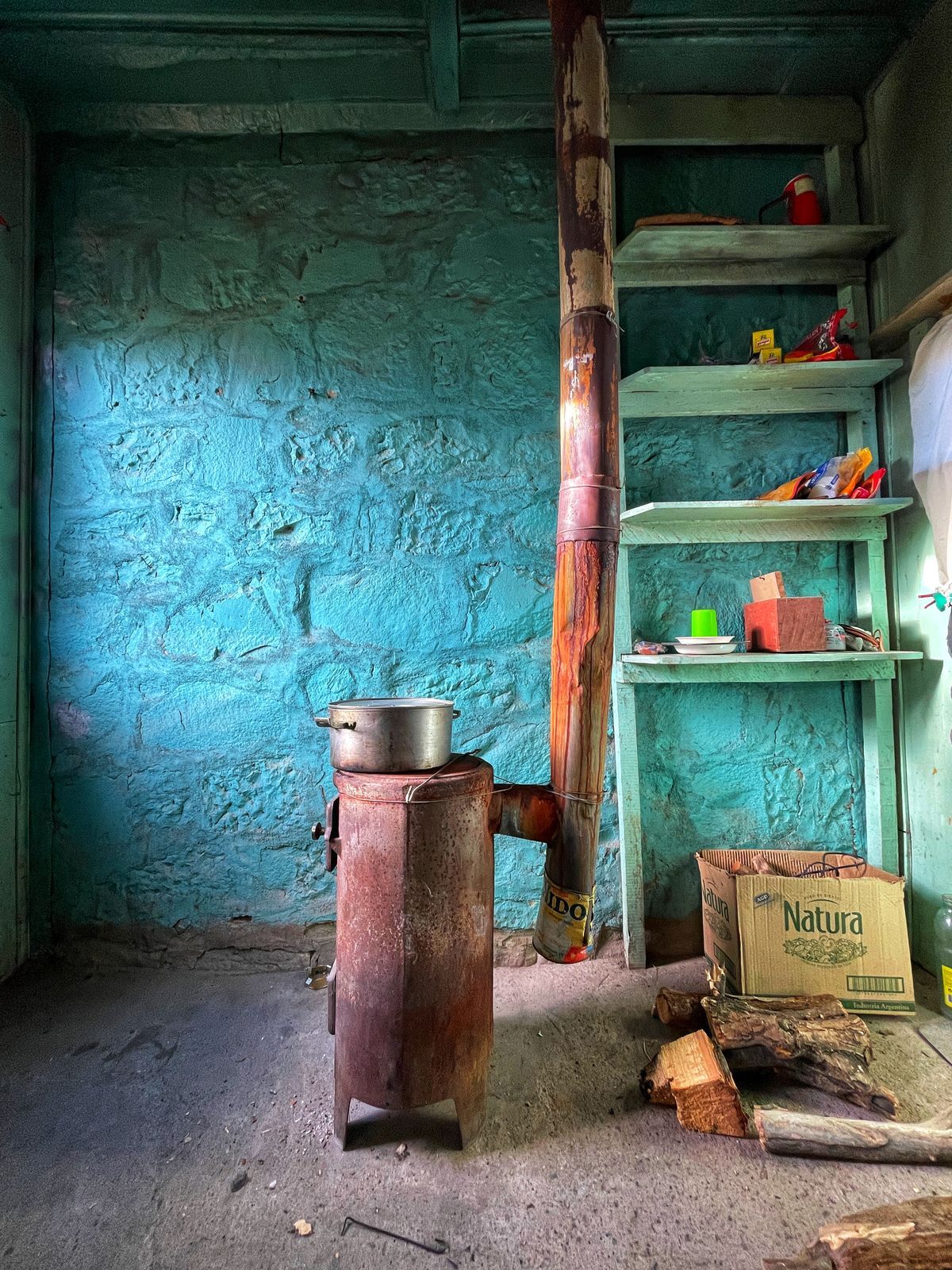

We drove about 20 kilometers a day for the first four stages, camping along the side of the road or in makeshift camps. Once we were put up at an estancia, one of Patagonia’s historic sheep ranches—sheep for wool and lambs for meat. Romero, our host, put us up in a cubicle with a bed and two mattresses, while a prewar wood stove served as heat and a cooker for the hard-boiled eggs, lentils, and rice that were the staples of our diet. To our surprise and amazement, Romero also gave us a bottle of red wine—I’m a teetotaler, he said, handing it to us. Dad and I looked at each other with sly smiles but decided to open it when we had a break.

Three days later it was time to uncork it. We had reached another Estancia, La Leona, which over time had also become Paradero - a place to stop and refuel where it was also possible to spend the night. From the walls, the solemn eyes of climbers who had become legendary for having opened routes on FitzRoy and Cerro Torre looked down on us. The gaze of Casimiro Ferrari and the Ragni di Lecco had been fixed on us since 1974, the year in which they were the first to place their flag on the summit of the Torre. After the first few days of training, it was time for the bionic man to unleash himself. We had covered half the route and had another 110km to go to El Calafate, which I estimated we would have covered in five days. Three were enough. To my great surprise, the wind left us alone and we managed to grind out stages of 34 and 37km. The Pampas offered chance encounters: with other people, like Oscar, a road maintenance man who invited us to his house to watch an Argentina game; and with dozens of animals, from guanacos gracefully leaping over cattle fences to desert foxes and condors.

So we reached El Calafate after nine days of walking; we had covered 213km. I was amazed at how easily Dad had slept in the tent, it had taken me weeks to get used to it! It was nice to look at the camp and see him nestled inside my historic house. The new one, the Namika, had a more slender silhouette and more robust poles, judging by the weight of the pre-connected tubes. Raised edges ensured optimal air circulation, so condensation was limited to the minimum - to date, after the first twenty nights, I have never found a drop of humidity when I woke up. The assembly was done directly by inserting the supports onto the waterproof sheet, without installing it afterwards on the basin, already secured to the outside wall with eyelets. In addition to being functional, it also seemed... Beautiful! I can't explain it, but perhaps after so much time spent sleeping under the stars my portable house must also have a nice appearance, and this one really made your eyes shine.

We stopped in Calafate for a few days and before Dad left we went to see the Perito Moreno, one of the glaciers that form the Campos de Hielo. The Perito is perhaps the most famous and certainly the most photogenic: from the panoramic walkways that stretch out in front of it, you can photograph it from all angles, capturing the blue shades of the ice and the walls up to 70 meters high. Rightfully, the site is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The next day it was time to say goodbye. I would stay another day, just long enough to do the shopping and cook food for the next march. In seven days I would cover almost 300 km and return once again to Chile for the last leg of the world tour on foot in America. Direction? The End of the World.