We met Nicolò Guarrera and Ezio, his faithful companion-luggage, at the end of Patagonia, after thousands of km traveled on foot on the Carretera Austral. A journey that began years ago with a couple of great ambitions: the first, above all, is to go around the world on foot; the second, adds the necessary slowness to the journey, to be able to enjoy the sense of so much road.

Let us be transported to this immense corner of South America by Pieroad's travel diary.

Patagonia: Between Imagination and Real Borders

What do you imagine if I say Patagonia? Dig into your memory, join the fragments of hearsay with the colored frames of adventure broadcasts lost in time. What do you find? Where have you been catapulted?

The world is round but if we lay it out on a map, Europe in the center, it seems to have two corners. Australia, fifteen thousand kilometers from Italy at the bottom right, and the tip of Latin America on the opposite side, an appendix of land jutting out toward the south to touch Antarctica: Patagonia. Two halves give it shape, Argentina to the east, crouched on the beaches of the Atlantic Ocean, and Chile stretched out behind it, back to back, looking at the Pacific and the last sunset of the day.

There are two roads that cross it, legendary tracks with the power to make your eyes shine with the feeling of freedom they manage to evoke. On Argentine territory runs the Ruta 40, the backbone of the country that connects the border with Bolivia to Tierra del Fuego. In Chile, the lesser-known Ruta 7 winds for 1,247 km from Puerto Montt to Villa O'Higgins, lining up microscopic pueblos so isolated that it seems time has stopped there sipping a steaming mate. The Chileans call it Carretera Austral: the road to the end of the world.

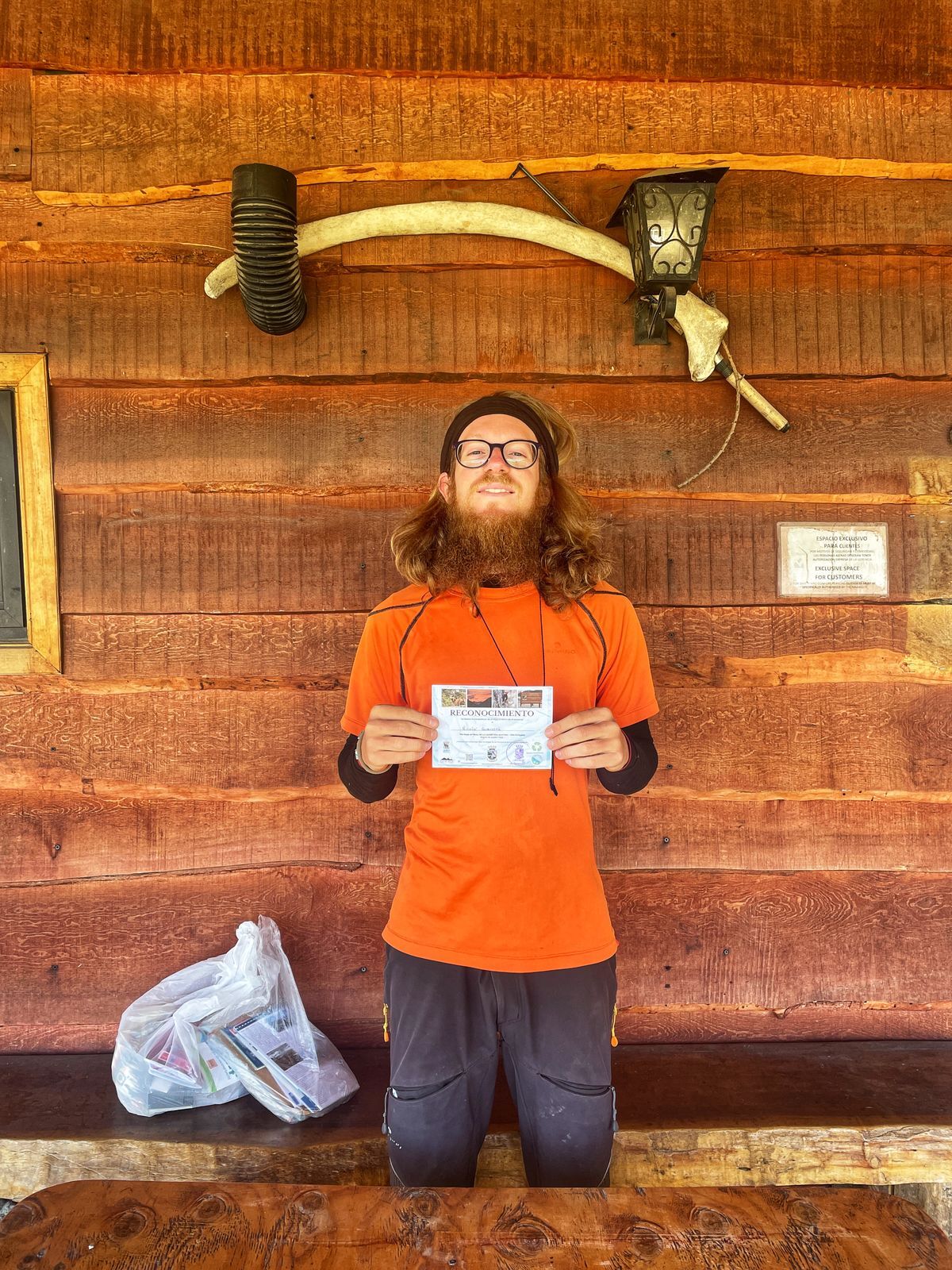

Hundreds of travelers travel it every year by motorbike or bicycle, some hitchhiking, others renting a car. Few, if any, have experienced it in the slowest and most human way of moving: walking. This year at least it seems we are the only ones, Ezio and I, an Italian and his stroller engaged in a world tour on foot. A 30,000km and five-year dream that halfway through its journey has brought us right here, at the gates of the Carretera Austral, directed by the passionate advice of dozens of people.

But what makes Chilean Patagonia so special? It is an isolated place, where the connection with Nature and people is stronger than that with the internet. In an area slightly smaller than Italy, seventeen National Parks protect eleven million hectares of land, safeguarding dozens of ecosystems that are completely different from each other and unique in the world. Patagonian woods and forests are home to a gigantic biodiversity and capture three times more carbon dioxide than the Amazon Forest. The Andes plunge into the ocean creating a mysterious labyrinth of fjords and unexplored glaciers give life to waterfalls, lakes and rivers of unreal colors. Two small Antarctics arise between land and sea: the Ice Fields, the largest glaciers on Earth, as large as Molise and Sardinia. And this is just the beginning.

Three months to reach the end of the world: the journey

I close the pages of the National Parks Passport and stop daydreaming for a second. The little book with the dark red cover collects this and other information about the road I am about to travel. I leafed through it before leaving, I like to study the route before venturing out; but now it is time to go. I am in Puerto Montt, above the sign that marks the kilometer zero of the Carretera Austral. I have three months to travel it, the time to use up my Chilean visa. Direction? The pueblo of Villa O'Higgins, seven hundred souls between snow-capped mountains and lakes on the border with Argentina. We walk south.

Leaving the city, the first National Parks of the Carretera Austral begin to appear. The Pumalin has an amazing story. An American entrepreneur and naturalist, Mr. Douglas Tompkins, fell in love with Patagonia in the 90s and after selling the shares of the company he had created, he began to buy land between Chile and Argentina. The aim was to save them from indiscriminate exploitation: mines, loggers and intensive farming were destroying these regions. The locals did not trust him and hindered him with all means. They did not understand what this gringo had come to do, buy their land and leave it there? To do nothing with it? Something did not add up. The picture became clear a few years later, when Tompkins united the properties purchased in different Natural Reserves, giving the possibility of visiting them to anyone who was interested. With his action he demonstrated that intact Nature was not only a resource to be consumed, but a world to be cultivated and shared. And that's not all. In the early 2000s, Tompkins decided to donate everything he had bought to Argentina and Chile, according to border limits, in exchange for the states’ commitment to create National Parks. It was the largest private land donation in history, something the size of Sicily, so to speak.

Pumalin National Park is one of the pieces of the legacy and today has campsites and dozens of trekking trails. I have done several of them, the most impressive of which is the ascent of the Chaitén volcano. From its summit, which exploded in a devastating eruption a few years ago, you can take in the entire width of Patagonia, all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The crater looks like a Dalí painting, a sandy desert from which black, lanky trunks emerge, what remains after the eruption. Inside the crater, the rain has formed a lagoon, in stark contrast to the arid and dry surroundings.

Continuing south, the landscape changes. This is the region with the most rainfall in all of Chile, lush vegetation forms the backdrop to solitary mountains with snow-capped peaks. September has just begun and it is still winter, these are rainy days. I am well equipped, a fire-red Valdez jacket protects me from the water for several hours. It has a heavy feel, so it also protects from the cold and wind, without however creating a layer of condensation. It would be the height of being protected from the water outside and then finding yourself soaked with sweat! An internal pocket holds my phone, I carry it on my body to count my steps, the count reads sixteen million. The jacket goes with rain pants, which are also very breathable. The only sore point is the shoes. The trade-off is between waterproofness and fit, I could wear hiking boots to avoid getting my feet wet but in doing so I would sacrifice the cushioning of soft rubber. I walk forty kilometers a day on asphalt, the solution would be a massacre for the joints. I breathe a sigh of resignation. At least my feet can dry.

I leave the Los Lagos region to enter the next one: Aysen. Chile is a very long strip of land - 5000 km as the crow flies between the northern and southern extremes - but it is on average two hundred kilometers wide. The regions follow one another from north to south, so they have been numbered to make it easier to order them. Aysen is the eleventh, so Los Lagos, where I come from, is the tenth. In this last region, Patagonia has a nickname, "the Green", because of the constant rainfall that waters the land every season of the year. I ask around if Patagonia also has an epithet in Aysen, but the answer is no. It will be up to us to do it justice and find it a nickname.

Villages and meetings

The pueblos are really tiny, most of them only a few hundred people live in. One of them is Puyuhuapi, on the shores of the fjord of the same name. The weather forecast calls for rain all week, so I decide to stop and wait for the clouds to clear. Before leaving home, my friends had convinced me to document my world tour on foot on social media and one of the consequences, both pleasant and unexpected, is that several people contact me on Instagram to offer me hospitality. It also happened in Puyuhuapi, so I'm headed to Javier and Magdalena's house. It's been two years since I left but it still feels a little strange to knock on strangers' doors and settle down on their couch for several days. I imagine it's the same for them, but even so the welcome is warm and in no time at all we become friends. I immediately decide to tempt them by the taste buds and in the evening I take over the stove: handmade gnocchi with grandma's recipe. If there is something I have learned on this trip, it is that an Italian in the kitchen is always a beautiful story to tell. Learn some home-made recipes and get involved: you can't imagine how many doors will open for you and the people you will meet. The kids are very nice and we break down the barriers of formality in the space of a couple of days. It happens that while I am with them the Fiestas Patrias fall, two days that celebrate national independence (September 18-19). Throughout the week there are parades, dances, and banquets of all kinds, we go together to the celebrations that are held in the pueblo, inside the spacious school gym - the flood stopped me, not the pueblo.

The time has come to move on, as always. After Puyuhuapi and a couple of even smaller villages comes Coyhaique, the regional capital where half of Aysen's population is concentrated. However, before reaching it, I pass through another National Park, Queulat. Inside it is the Ventisquero Colgante, a tongue of ice hanging in mid-air that originates from the glacier of the same name. Years ago it reached the mint-colored lagoon that lies beneath it, but due to global warming in recent years it has receded hundreds of meters. Just the day before I arrived, an enormous mass of ice broke away from the Ventisquero, shattering into a thousand pieces. Knowing the sad fate of this and all the other glaciers in the world gives them a dramatic, fragile beauty. How many more people will be able to visit them? And how will they see them if they are already mutilated, heroes of a war they can neither fight nor win?

It is with these thoughts that I arrive at the regional capital a week later - that is how long it takes me to cover 250km. Coyhaique in the Chonos language, the original people of here, means "between the lakes". I'll let you guess the reason. I don't stay there long, a couple of days to rest and do some shopping. It will be the last city I visit for the next two months: it means difficulty in supplies, scarcity of fresh fruit and vegetables and high prices. I load kilos of quinoa, dried fruit and dehydrated food, thanks to Ezio I can carry up to 50kg - equipment included. Then I set off again, sweating at every climb for the load I have to push.

Breathtaking views open up on the sides of the Carretera Austral and every time I reach a town I am welcomed with open arms by someone. I come across some travellers on motorbikes, very few on bicycles, summer has not yet begun. An immense peace fills my lungs with every breath and at certain moments I find myself listening to the wind more attentively, with my gaze lost in the void. This place echoes with a music that plays with the rustling of the branches and the chirping of the squat chucaos. The harmony brings us back to the natural dimensions of things: the immense mountains, the small man, the impetuous force of the river that waters the woods.

One day I take a detour to Laguna Leones, a little gem unknown even to most of the local population. I arrive there after several hours of trekking, after camping in a large grassy clearing. The absence of people allows you to feel a solemn vibration in the air. Behind the lagoon lies the legendary Northern Ice Field, a land that no one has ever managed to cross. A single settlement, located on the northern end, houses the forest ranger of the Exploradores Glacier, one of the many that make up the Ice Field. Antarctica, in comparison, seems almost crowded. Knowing that no one has ever succeeded in the feat of crossing it all gives it the charm of an unconquered goal, in spite of the tenacity of man and technology. Nature is still powerful and here you can feel it immediately.

The beauties are endless and can be appreciated even in encounters with simple people. In Cochrane I am hosted by Raquela and every morning we find ourselves sipping hot mate in front of the wood stove, the kitchen and heating of all the houses in Patagonia. The mate is a small container in which you drink a bitter-tasting infusion, yerba mate. You fill it halfway with yerba and after having tilted it you place the bombilla - a metal straw - under the yerba so that it does not move; finally you pour hot water. This operation is called cebar and is carried out by the person who prepares the mate, filling it with water from time to time because the mate is small and is barely enough for three or four sips. Every time the water runs out, the mate goes back to him, who pours and passes it to the next person, onwards until everyone has drunk. Once everyone has drunk the round begins again and continues until the water is finished. Whoever is satisfied and doesn't want any more says thank you; and skips the turn.

Villa O'Higgins

The last 220km begin from Cochrane. A ferry halfway takes you from one bank to the other of Mitchell Fjord, one of the four that you meet along the Carretera Austral and for which you need to embark. October is ending and I'm about to arrive in Villa O'Higgins, the last pueblo of Ruta 7. It is an isolated village, over a hundred kilometres from the nearest inhabited centre. It is surrounded by high mountains, a natural border with Argentina; and long lagoons with spectacular colours. For two months Patagonia has filled my eyes with its wonders but once again it decides to leave me speechless. Villa O'Higgins is a jewel set among the Andes and the miradores on the hills of the eastern side let your gaze wander over the enchanting surroundings until it cuts across the blue waters of Lake O'Higgins and you imagine arriving on the other side, in Argentina. This time I decide to stay in a hostel, El Mosco, a meeting point for those who want to cross the border. Three couples of cycle travellers arrive and leave while I am here, together with them we retrace in our memory the salient points of the most beautiful road in Patagonia. Once we say goodbye, I go out onto the wooden veranda with a Wild West feel and sit on the bench to savor the last moments of Chile. Martin, the boy who runs the hostel together with Fili, is raking the gravel of the entrance path. The metallic sound of the stones against the iron is lost in the large garden where a couple of tents were set up a few hours ago. On the left you can guess the entrance to the valley of the Mosco Glacier, while on the right, further ahead, the mountains head towards the horizon, between white and blue. Patagonia…