What was an unexpected challenge you faced while traveling on foot, and how did you overcome it?

When I started writing these answers I was waiting for the visa for Pakistan, the bottleneck of the world tour on foot. For years I had been thinking about how to overcome it because the passage from Pakistan to the next country, China, Afghanistan or Iran, is a particularly difficult area, especially when moving on foot. I had lost dozens of nights there and over time a dozen scenarios emerged, all considering being already in Pakistan. Against all odds, however, the visa for Pakistan was issued for only 30 days, too few to cross it on foot. I had to change my itinerary: I will head south towards Surat, a port on the Indian Ocean, and from there I will embark for Oman.

Studying the route is important, especially if you go on foot. Making up for a delay by moving at a rate of 45 km a day sometimes becomes impossible, so it is necessary to move in advance and get an idea of where you are going. Even so, as in the case of the Pakistani visa, there remains something that does not depend on us. It is not an excuse to do without preparation and set off in a rush. You have to find a balance: remember that the unexpected, by definition, cannot be predicted; but that with good preparation and a certain degree of flexibility, you can turn even an unexpected situation to your advantage.

As an advocate for exploring the world on foot, how do you ensure your travel is environmentally sustainable?

When abundance is lacking, we get used to consuming less, perhaps just the right amount. Waste is reduced, for example of water and especially in the desert: with a couple of liters a day we can cook, drink and take care of basic personal hygiene. The logistical factor leads to a decrease in meat consumption, because without a refrigerator we cannot carry food that perishes quickly. Finally, recycling and repair become essential, often we have to wait weeks before arriving in a large town where we can stock up on materials; for this reason we learn to take care of what we have and find creative solutions.

In Australia one of Ezio's tires got torn when we were a month away from arriving in the city. I fixed it with a generous bandage of duct tape and gauze, the kind for wounds, and in that condition we were able to walk the next day. Without much hope, I went to rummage in a dump along the road and one day, with a stroke of luck, a tire of the

You have tried many cuisines during your travels. Which food from which country surprised you the most?

Without a doubt the “green”, in Ecuador, a country unknown both to the great tourist traffic (aside) and to international cuisine. The green is a type of banana that must be cooked to be consumed, it has a faint flavor and is used as a side dish and base of many dishes. Probably the most inflated is the tigrillo: the green is boiled, mashed and fried together with eggs, so that it takes on an orange color - hence the name, because of the tiger. Then salty cheese is added, but there are those who prefer the chicharròn, pieces of fried pork fat and skin. A bomb of flavor and energy, cost: one euro and fifty.

How do you deal with language barriers, and have you learned any new languages or dialects during your travels?

The first three years went smoothly between English and Spanish, it is fun to learn some expressions in the local dialects to personalize communication. In India the first, consistent difficulties arose. No relationship with the known languages and, surprisingly, even the sign language has changed. The Indians shake their heads continuously, so “yes”, “no”, and the nod of greeting that is done with the head are mixed up and already introducing oneself becomes complicated.

However, what is surprising is understanding that in addition to words we also have different ways of thinking, therefore of communicating: learning a few sentences or using an automatic translator have extremely limited practicality. I say “surprising” because at the beginning I was amazed by the distance I perceived when trying to understand a person in India and make myself understood. The logical paths are different, therefore to get to ask something that the other person doesn't know, the reasoning that you have always used and has always worked is useless this time - and you have to understand that it is without the other person telling you.

In some cases it was impossible even to ask to pitch the tent by indicating the place in front of us. Even a smile, which I thought was part of a universal language, had lost the ability to speak.

Can you share a story where the way of life of a local community had a profound impact on your perspective or philosophy of travel?

In Europe we are used to great monuments: cathedrals, castles, aqueducts. In Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia the vestiges of the Incas and the peoples who preceded them survive, Macchu Picchu is the most famous example but another impressive work is the Qapaq Nan, the system of roads used by the sovereign's messengers, thousands of km up and down the Andes. The Inca empire extended roughly to Santiago de Chile, in the south, where the Mapuche resistance put a decisive stop. Here begins the change of perspective.

The Mapuche have lived in the Central Valley of Chile for hundreds of years, yet they have not erected any monuments. Why? Because for them, nature was the most beautiful wonder and it was not worth getting rid of to make room for imposing buildings. Forests, rivers and waterfalls became their sanctuaries, sites to protect and guard. In that part of Chile, ancient plant species such as the Araucaria survive; and the oldest trees in the world have been found, 5,000-year-old Alerces, correcting the primacy of the American redwoods. What would the European landscape have been like if our ancestors had had the same gaze?

How do you balance using technology to share your journey with the desire to be fully present?

It's a balancing act. Since I've been in India, with a stable connection, the issue has become delicate. I tried to leave the times of use vague, but it didn't work. I find it better to establish conditions of use, for example avoiding looking at the phone during downtime. Technology serves a purpose, every now and then it needs to be repeated and remembered how to use it to reach that goal. In my case, gathering information, sharing the journey and communicating with friends and family. Nothing else. If I have to mess around I do it, but not on the phone. In this way the use is reduced to the essential or little more and you can spend more time looking around.

Aside from geographic destinations, are there any specific experiences or personal goals you aim to achieve in your future travels?

One day I will return to Latin America to meet the people I met on the road. A friend from college has started a tiny community in the Amazon Forest. I would like to go and give him a hand, live for a while at a different pace, without desires. But my biggest dream is to write a book about walking around the world. It is the only certainty of when I will return.

What advice would you give to someone who dreams of embarking on a similar journey, but feels hesitant or uncertain about taking the first step?

Reading is the first journey of life, the wild and impossible race of fantasy. I would say to start with books, reading about people who have done things similar to what you dream. Let yourself be transported, but also understand if it is what you really want. Often we desire things that do not belong to us just because they are fashionable and are sold in an attractive way. Thirty years ago traveling was an unusual way to invest time and money, today it has become a status symbol.

I recommend talking to people who have had experience, trying to empathize with the difficulties, above all. Then comes a time when you have to throw yourself in, when you feel prepared. You will never be ready, because the real journey changes you and the change undermines what you thought of yourself and the world. If you accept the idea that it can happen, then go.

India: a country with a thousand facets, in one sentence what was it like to cross it on foot?

It was like watching an open-air movie staged without the actors knowing.

I have only traveled through some regions of northern India, had I been elsewhere the projection would have been different. However, something suggests that in every corner, at every moment, something ancient and, for this reason, rare is happening.

What advice should be kept in mind for those who are embarking on a similar venture in this country?

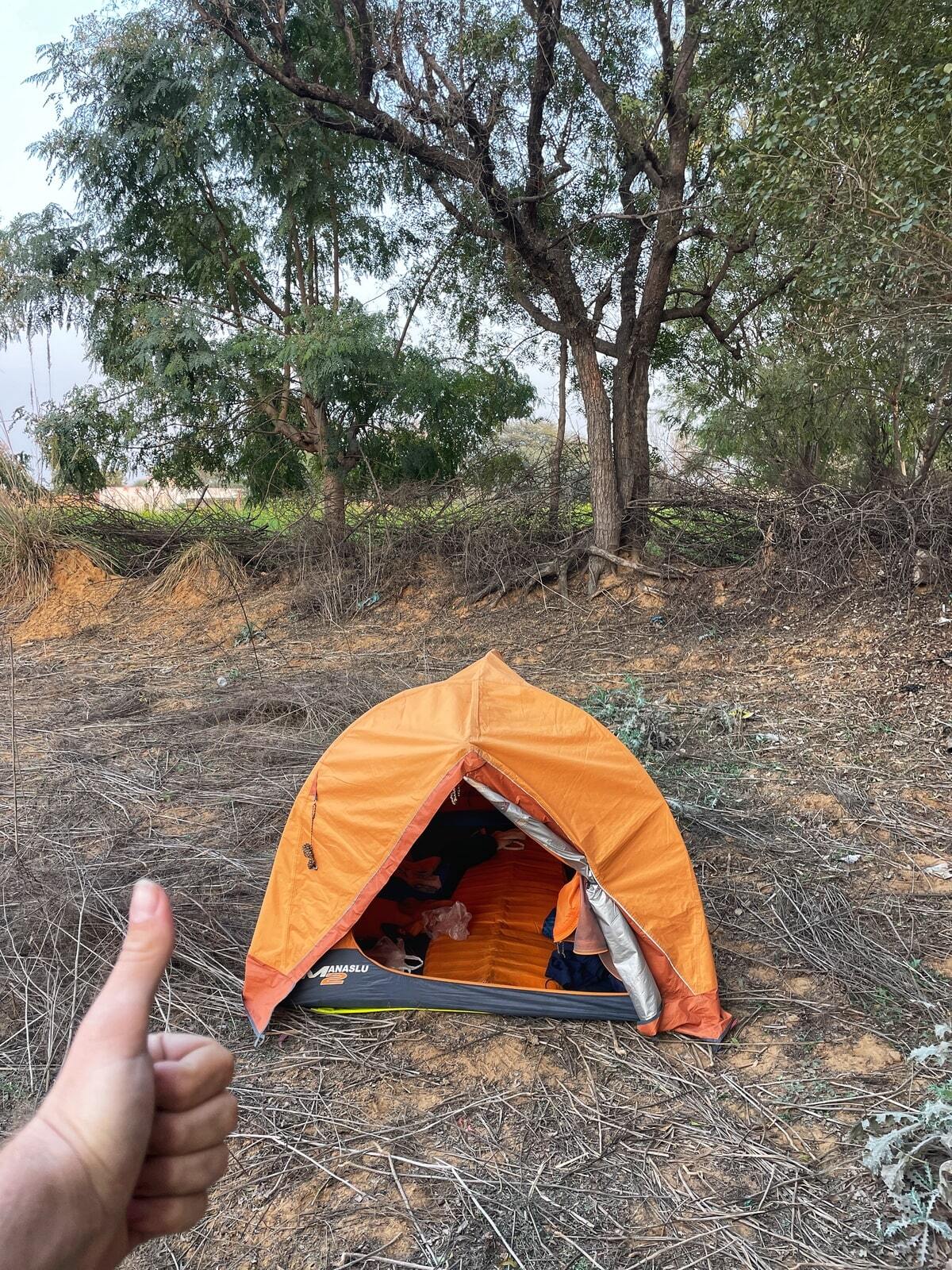

First the technical advice, the easy ones. Locals don't use toilet paper, so stock up on it in the big cities. Drink only bottled water, mechanical filters don't make tap water or well water drinkable. If you spend a lot of time on the road, get used to the horns in your eardrums quickly. Get used to the inquisitive looks quickly too. Many hotels and guesthouses don't accept foreigners because you need a special form to register them; forget about free camping, there are people everywhere and every time you stop you will be attacked by a crowd of curious onlookers. In four months I managed to do this only three times, hiding in the bushes or in a forest. You can haggle over everything, even when the prices are written; shopkeepers and street vendors will ask you at least double what a local would pay.

General advice, let's say for approach, is to stay calm and try to let go. Meetings, especially on the street, work differently. You will find yourself losing patience every five minutes if you get defensive. Let it go, don't take it personally but be firm, otherwise you will be overwhelmed. People are not ashamed to throw their misery in your face or to leverage your pity. Arm yourself with a notebook and take note of everything you find strange, out of place, magical or tragic. The rituals are still powerful and alive and abundant. Fill your eyes well.

What are the things that struck you the most? Landscapes, people, cultural aspects?

The amount of people is crazy. There is someone around at all hours, whether in the city or in the countryside. As soon as you stop you are surrounded by a crowd of onlookers who cancel the physical distance, touch you, stare at you, without caring how you might feel. They had told me it would happen but I didn't think it would be so strong. At times, I found it violent. Coming from the desert certainly didn't help, it was a drastic change of perspective.

Alongside, with silent complicity, are the free animals: the omnipresent cows and water buffalo, stray dogs, baboons and macaques, goats in abundance, some sheep, wild pigs, horses, donkeys, dromedaries in the desert regions. It is comforting to note that the massive human presence has not eradicated other forms of life. People and animals coexist peacefully, without giving each other weight.

The approach to such a rich culture is the door to a further world. You have to come here to realize that there really is more than what we think we know. Life is lived differently, with other horizons, and the keys to reading reality are different.

In any case, I remember having crossed a small part of the Indian microcosm, the regions of the Northern Plains, and in a relatively short time, just four months. Had I lived in other areas, I would probably have different memories.

The next steps? And how will you tackle them?

I am on my way to the city of Surat, 1100 kilometers from Delhi. I plan to arrive there by the end of February, using the time left on my visa. I will then embark for Oman, praying to find kind people at the reception: Ezio is always a lottery.

From Muscat, the capital of Oman, the ascent of the Arabian Peninsula will begin: Al-Hajar mountains, Arabian coastal desert, Kuwait. After a brief transit in Iraq, the Zagros chain, in Iran. These are the next six months. It must be said, visas permitting.