Cycling beyond borders, for yourself and others: an interview with Centoventuno

There are journeys that begin with a dream and grow with determination, friendship, and a greater cause.

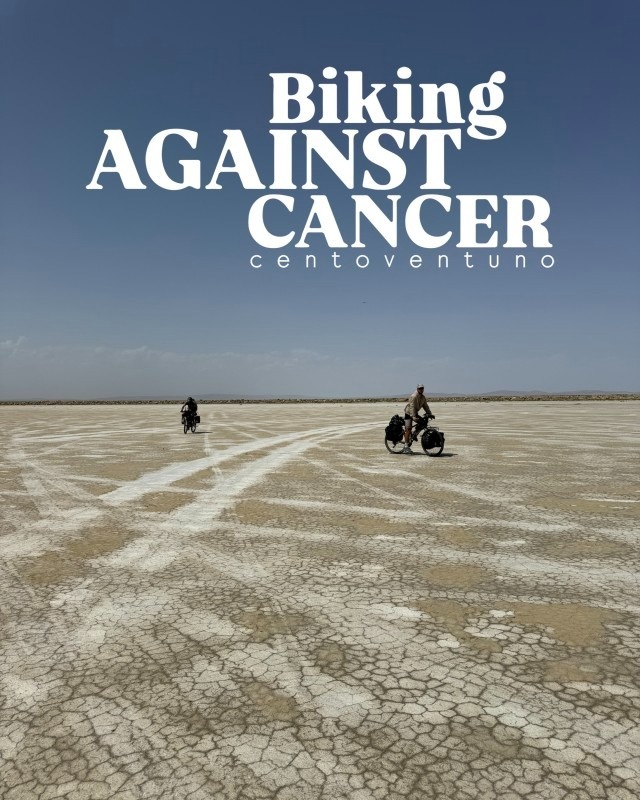

This is the case of Centoventuno, the project of Andrea Incarbone and Giacomo Perone—two friends and fellow bikers—who decided to cross the world from Turin, Italy, to Adelaide, Australia, pedaling for cancer research.

Ferrino believed in them from the beginning, supporting them in choosing the equipment to face extreme climates, remote routes and unknown territories.

We reached them during one of their rare breaks, a few months before their arrival, to have them tell us how it all began, what it means to pedal for a cause, and how a dream transforms — kilometer after kilometer — into something much bigger.

How did the idea for "Biking Against Cancer" come about? Was there a specific moment when you realized this trip really had to happen?

Our dream began in 2019, when we took our first bike trip from Turin to Venice with the scout group. It all started from there: the following year we went to Palermo and then we told ourselves we could dream bigger, even imagining a Turin-Adelaide trip.

In 2021, Andrea's mother's diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer intertwined our story with that of Bike Against Cancer. Every spring we considered leaving, but our conditions were never stable. Only in 2023 did we manage to reach the North Cape, and after Silia's passing in November of that year, we knew it was time.

In 2024, we finally set out, dedicating the entire trip to her and launching a fundraiser together with the Veronesi Foundation. Thus, Bike Against Cancer was born.

We chose the Veronesi Foundation specifically because it actively engages in research and experimental therapies, such as those that, in Silia's case, allowed her to live another three years with her family.

These treatments not only prolong life, but also make the patient's journey more peaceful and enjoyable, compared to more invasive standard therapies.

We've seen the value of research firsthand, and supporting those who work every day to make it possible seemed like the most natural way to give our journey a deeper meaning.

How many days did the trip last, how many kilometers did you travel, and how did you organize the stages?

The journey began in April 2024 and will end in late September 2025. So far we have cycled 20,000 km through 25 countries, with the last 3,000 km to go in Australia.

We chose the states based on our interests and then divided the route into stages, aiming for the large cities or areas we wanted to cross.

Over time, it became easier to organize ourselves, learning to understand our rhythm and capabilities day by day.

When did you feel the strongest sense of purpose behind the project, despite the effort?

Certainly a few weeks ago, in Bali, when we reached the 33,000 euro milestone: the amount that will allow us to finance a research grant for an entire year.

It was a turning point. We realized that Bike Against Cancer wasn't just our journey anymore, but something concrete, real, that was truly helping.

What does it mean to you to ride for such an important cause? How does your motivation change when the journey is also a social mission?

We can't imagine Turin–Adelaide without Bike Against Cancer. The two are intertwined.

Thanks to social media, we constantly receive messages from people undergoing treatment or who have lost loved ones. We've also frequently spoken with patients' families—some still in treatment, others who sadly passed away—and with the patients themselves, and each time this connection has given us strength.

Furthermore, one of the most beautiful things has been the exchange with researchers. Many are our peers and write to tell us that, thanks in part to projects like ours, they find new motivation in their work.

When they tell us “thank you, you give us strength,” we realize that our pedaling reaches much further than we imagine.

In difficult times, it's precisely these connections that give meaning to the struggle. We feel like we're doing something that goes beyond just the two of us and our bikes. It's a network of people who support each other, and it's one of the strongest motivations that accompanies us every day.

How do you plan such a long adventure? Can you tell us what the behind-the-scenes work was like?

We learned from previous trips, but this time everything was more extreme: different environments, variable temperatures.

With Ferrino, we've developed a hybrid, versatile package: lightweight yet protective tents, cold-weather sleeping bags, a stove, and a water filter—all designed for maximum autonomy.

Another challenge was visas and the geopolitical situation. We couldn't pass through Iran, so we detoured through Georgia and Russia, adding 1,000 km to the route.

We also obtained a visa to enter India via Pakistan, a process that is not simple but essential to avoid flying.

And then there's the unexpected. We had everything planned, but in Tibet, for example, we discovered that independent access was prohibited. We had to cross it by train, 600 km, and then continue cycling in Yunnan.

Travel teaches you to be flexible: the important thing is to leave prepared, but also ready to change everything at the last minute.

Was there a place, an encounter, or a landscape that left an indelible impression on you?

The Pamirs, Tajikistan. One of the toughest and most memorable parts of the trip.

We traveled the Bartang Valley, one of the most remote and least traveled roads. Two weeks completely off-road, with no internet connection and almost no one to see.

We climbed passes over 4,000 meters high, surrounded by 6,000-meter peaks, completely independently.

There we understood that what remains most deeply within us is the experience in nature, in isolation, far from everything.

Have you faced any physical or emotional challenges along the way? How did you overcome them together?

There have been many, but one of the toughest was on the border between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, during a snowstorm at 4,000 meters. We were late with our visas, tired, nervous... we even argued. Then, in the storm, a soldier told us the pass was closed.

We ended up in a container without electricity, in the dark, for 18 hours.

The next day, with the sun shining, we started pedaling again. In those moments, you need to listen to each other, respect each other's space, and be willing to communicate.

It's hard, but sharing all of this with someone who feels the same emotions makes the experience priceless.

What was the strangest or most unexpected day of the trip? An unexpected turn of events, a bizarre encounter, a memorable moment?

In Laos we stopped for a week to build a raft with bamboo canes and water bottles to cross the Mekong.

We loaded up the bikes and sailed for two days. The real concern wasn't the dangers of the river, but the fear of losing our bikes!

In the end, even after being sucked into rapids and tossed about, the raft held firm.

Then the military arrived and seized it… but it was an unrepeatable adventure, an absurd dream that we will remember forever.

What's the simplest thing that's brought you the most joy along the way? A coffee, a sunset, an unexpected gesture...?

In Russia, where you can't withdraw money with European cards, we miscalculated the amount. We were left with almost nothing.

A young man, seeing us in distress, slipped 20 euros into our pockets. We tried to refuse, but he insisted.

They allowed us to eat and drink for two days, until we left the country.

Then we decided to donate that amount to Bike Against Cancer: a small gesture, but full of humanity.

If you had to describe this experience in one sentence to carry in your backpack for your next trip, what would it be?

Experience the world out there firsthand, always listening and without prejudice.

And trust the effort you put into things: if it's genuine, sooner or later life will give it back to you.